Is soup a meal?

Soup feeds conflict, not people

In my household, soup is a recurring source of conflict. From time to time, my partner, Rachel, will offer to cook dinner, only to serve soup instead. These incidents have sparked lively debates about the meaning of the word “meal” and sharing of domestic responsibilities (are we really sharing cooking equally if one of us is serving water?). The advice of friends and colleagues was of little help in resolving our domestic strife: many of the people in my day-to-day life, most of whom are men, shared my concern about my partner’s misleading meal-related statements, while people my partner consulted---mainly women---also believed that the value of a meal is undiluted by literal dilution. These informal discussions, together with the results of a pilot study conducted last year, led my partner and I to wonder whether gender differences in soup-related attitudes and beliefs might be part of the source of our conflict.

Methodology

We carried out a gender-based analysis of soup-related attitudes and beliefs using a short online survey. The survey consisted of a landing page asking “Can soup be a meal on its own?” after which respondents were presented with examples of foods which are often served in bowls and asked to classify them as soups or non-soups. (These follow-up questions were mainly designed to identify respondents who lacked a basic understanding of soup.) In addition to these soup related items, we also recorded the gender of each respondent and provided an opportunity to self-identify as a person with a large appetite.

Results

Makeup of our sample

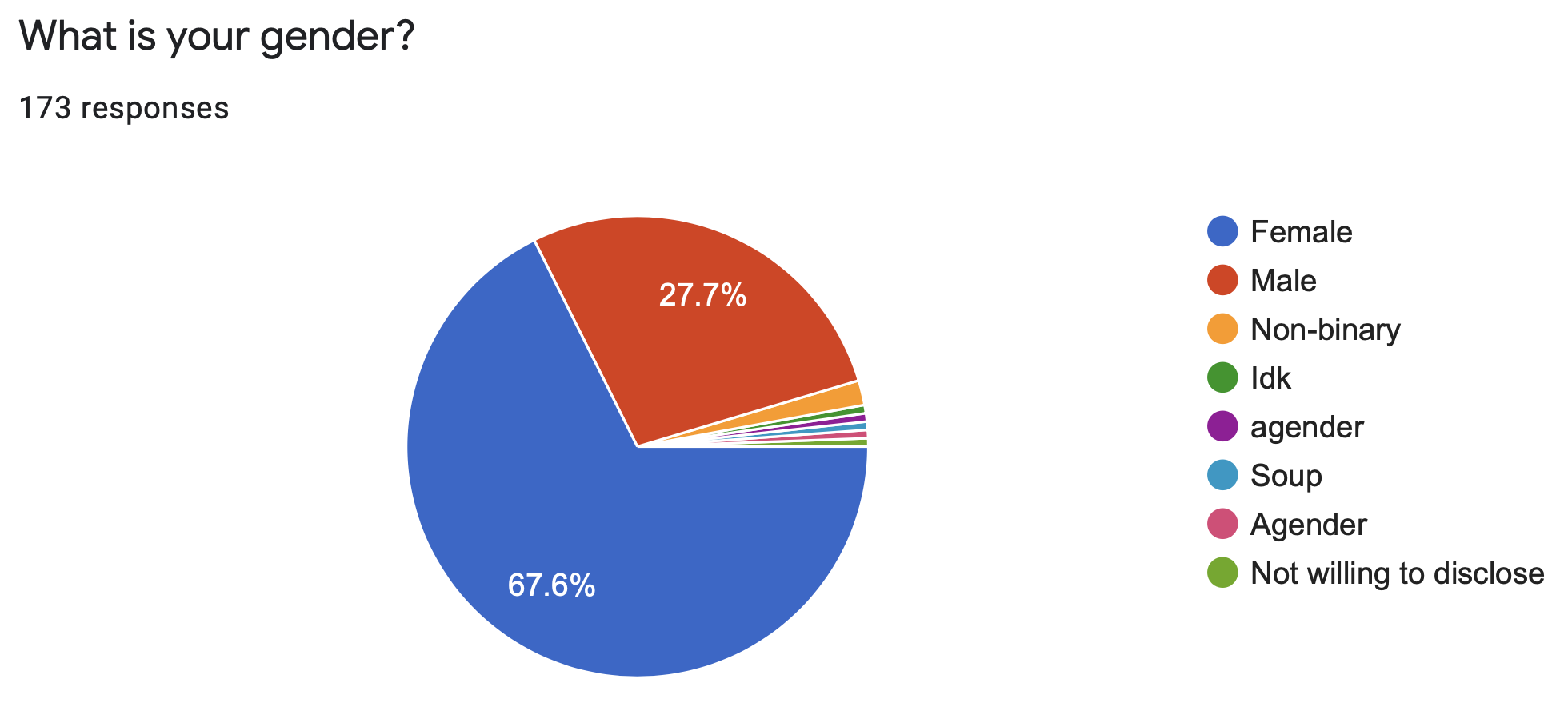

Our survey received 173 responses, the majority of which were from people who identified as women (117 respondents, 67.6%). We received a significant number of responses from gender diverse people (8 respondents, 4.6%), including three who identified as non-binary and one who identified as soup.

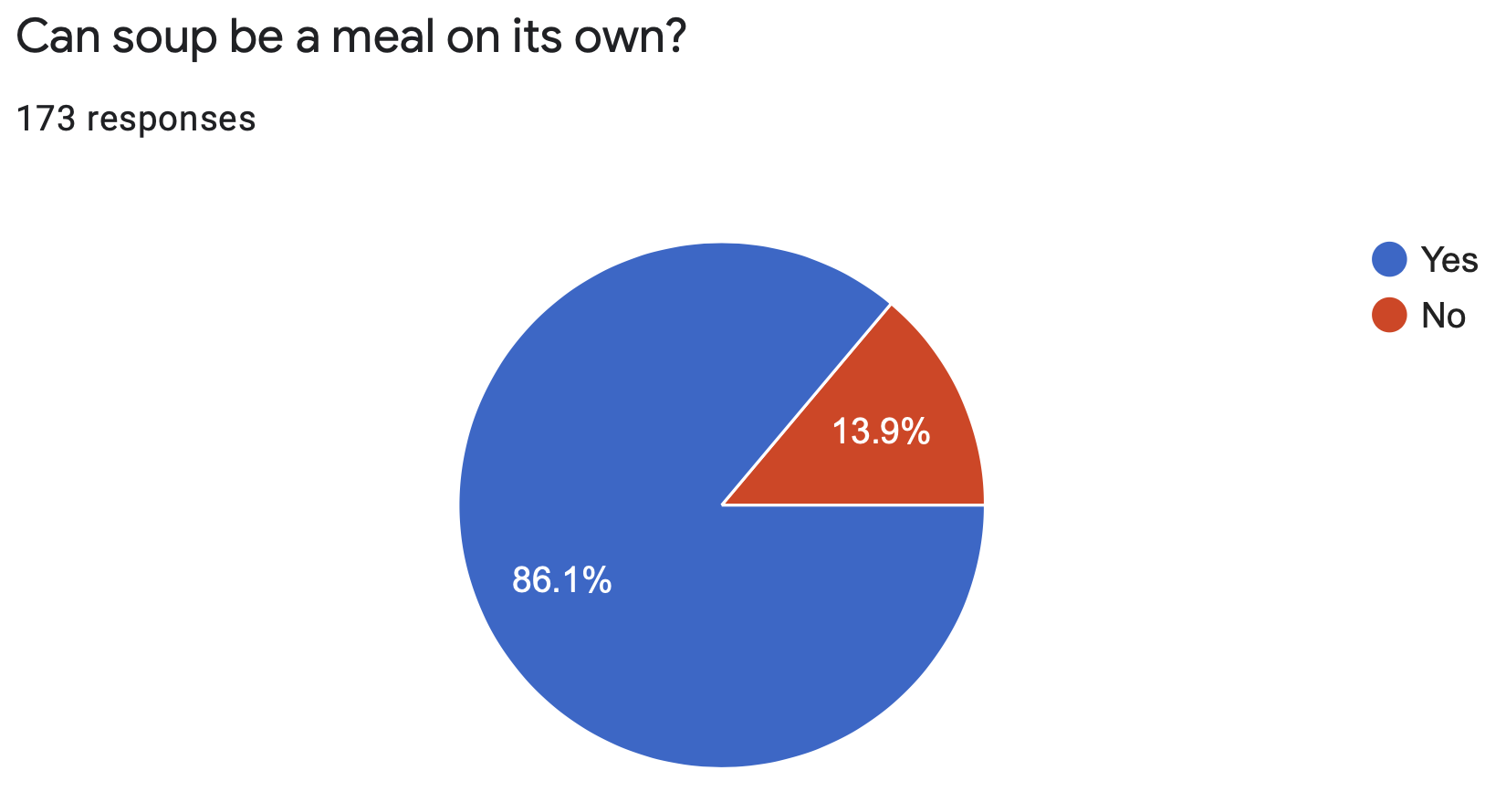

A significant minority of our respondents said that soup could not be a meal on its own (24 respondents, 13.9%).

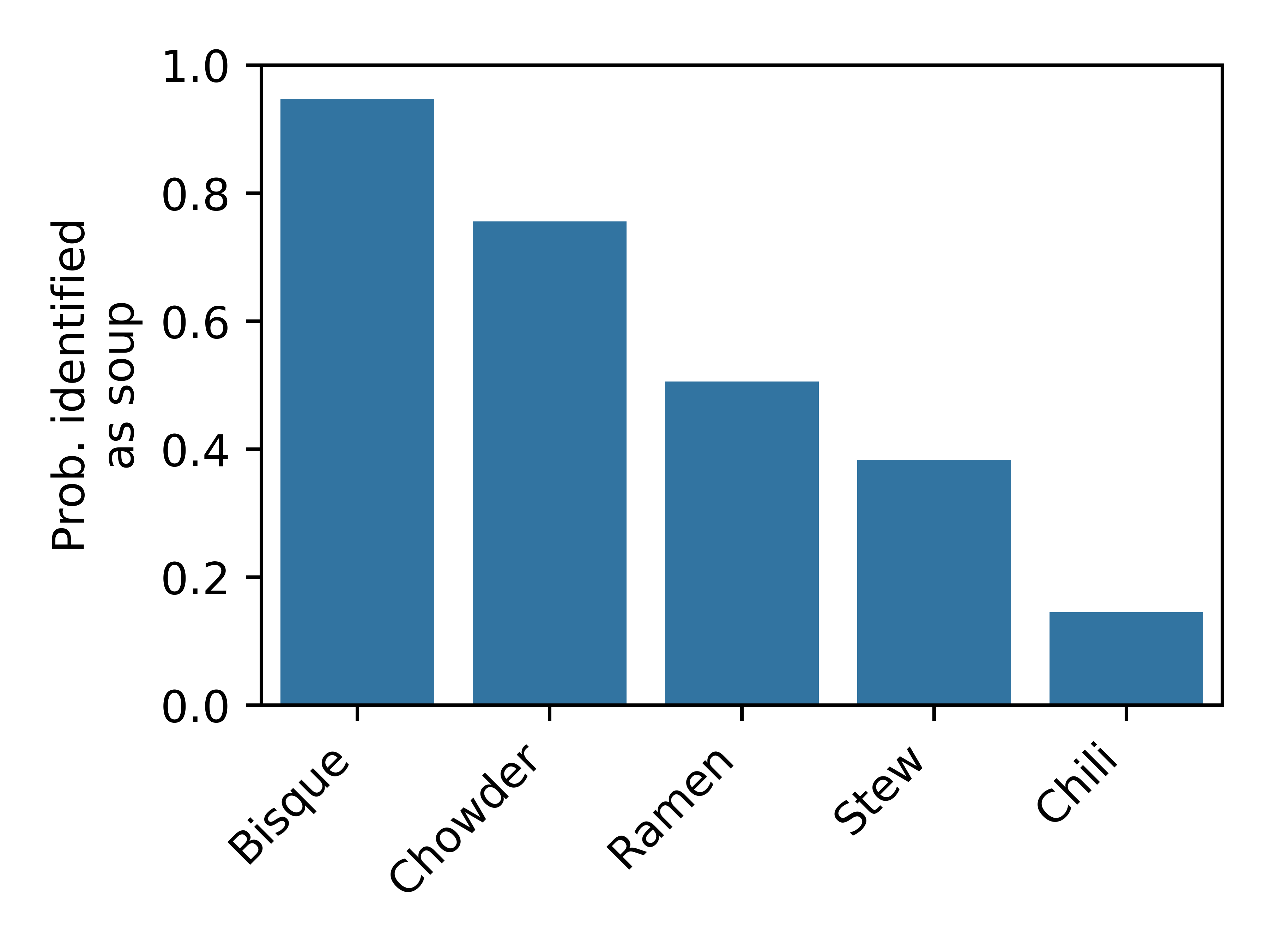

A concerningly large number of our respondents lacked a basic understanding of soup (33 respondents, 19.1%). In the bowl food classification task, these respondents either failed to correctly identify our positive control (tomato bisque) as a kind of soup (9 responses, 5.2%), or mistakenly labeled a bean-based dip (chili) as soup (25 responses, 14.5%).

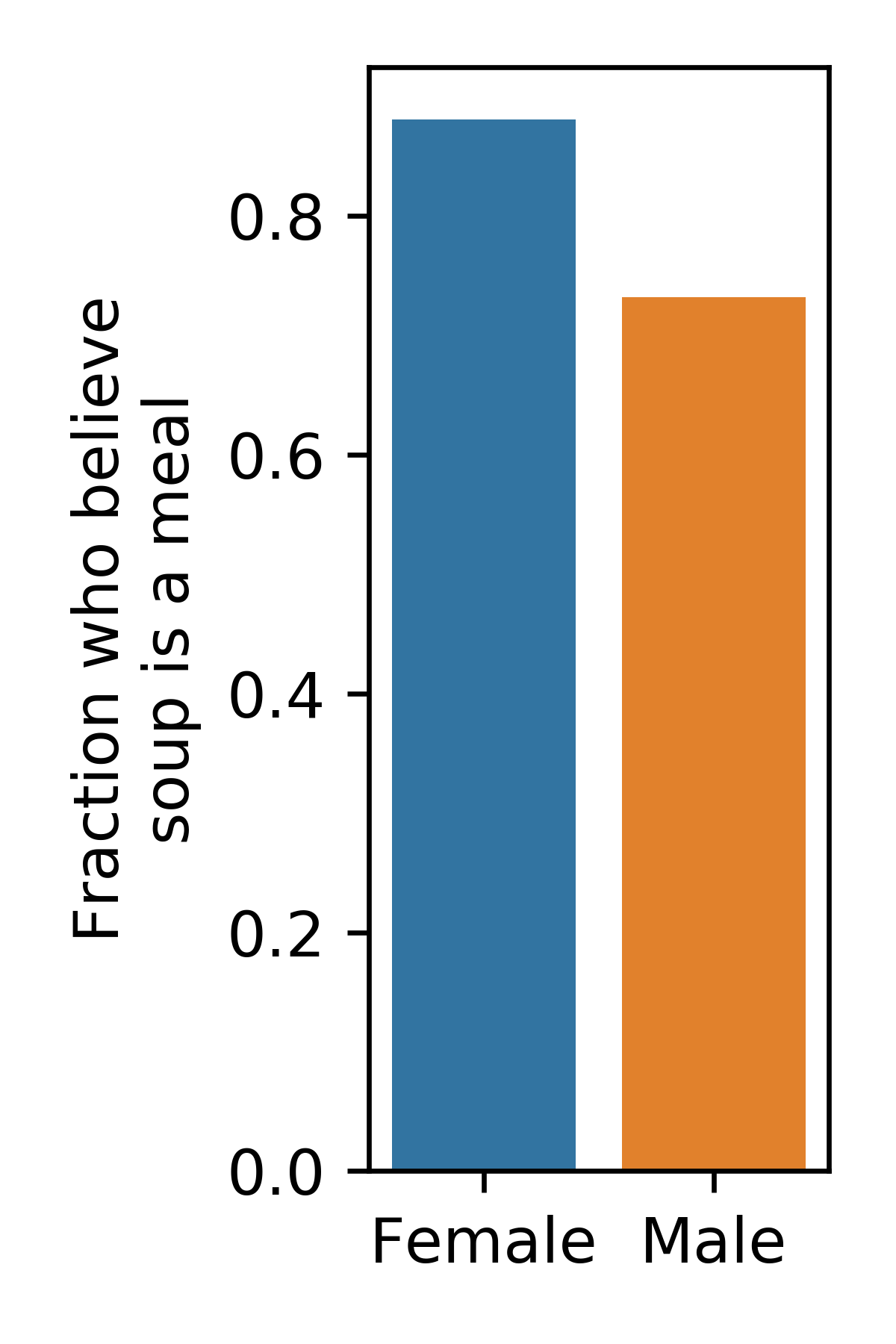

Gender-based analysis of soup

To understand the relationship between demographic factors and soup-related attitudes, we analyzed a restricted dataset consisting of respondents who identified as either male or female and who were able to differentiate between soups and other kinds of food served in a bowl. In this restricted cohort, women tended to be more likely to believe soup could be a meal on its own (Chi-squared p=0.0602).

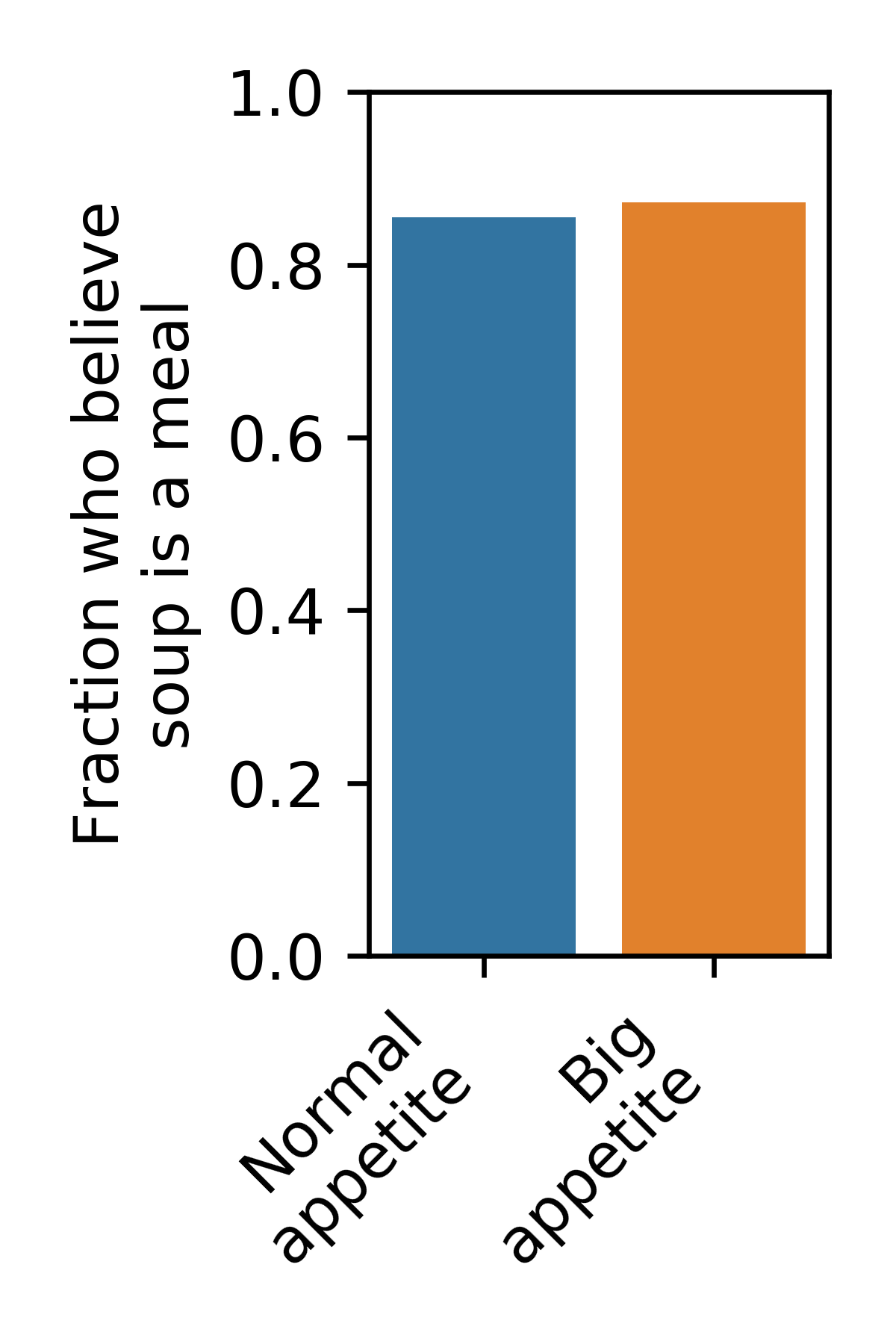

Following our pilot study, in which a similar trend was observed, many friends and colleagues suggested that the apparent association between gender and belief in the nutritional value of water might be due to an underlying difference in caloric intake. However, even though male respondents to our survey were significantly more likely to self-identify as having a big appetite (Chi-squared p=0.00150), there was no relationship between self-reported appetite and soup belief in our cohort as a whole (Chi-squared p=0.976). To explicitly test whether the trend-level association between gender and soup belief could be explained in terms of appetite differences, we concocted a logistic regression model of the probability of believing that soup is a meal as a function of gender identity, appetite, and their interaction. Using this model, we found that after controlling for appetite there was a significant relationship betweeen gender identity and the belief that soup is a meal (likelihood-ratio test p=0.023).

Incidental findings

Relationship between stew and soup belief

In the soup classification task, we asked participants which of the following five foods---all of which are typically served in bowls---are soups:

- tomato bisque

- corn chowder

- ramen

- stew

- chili

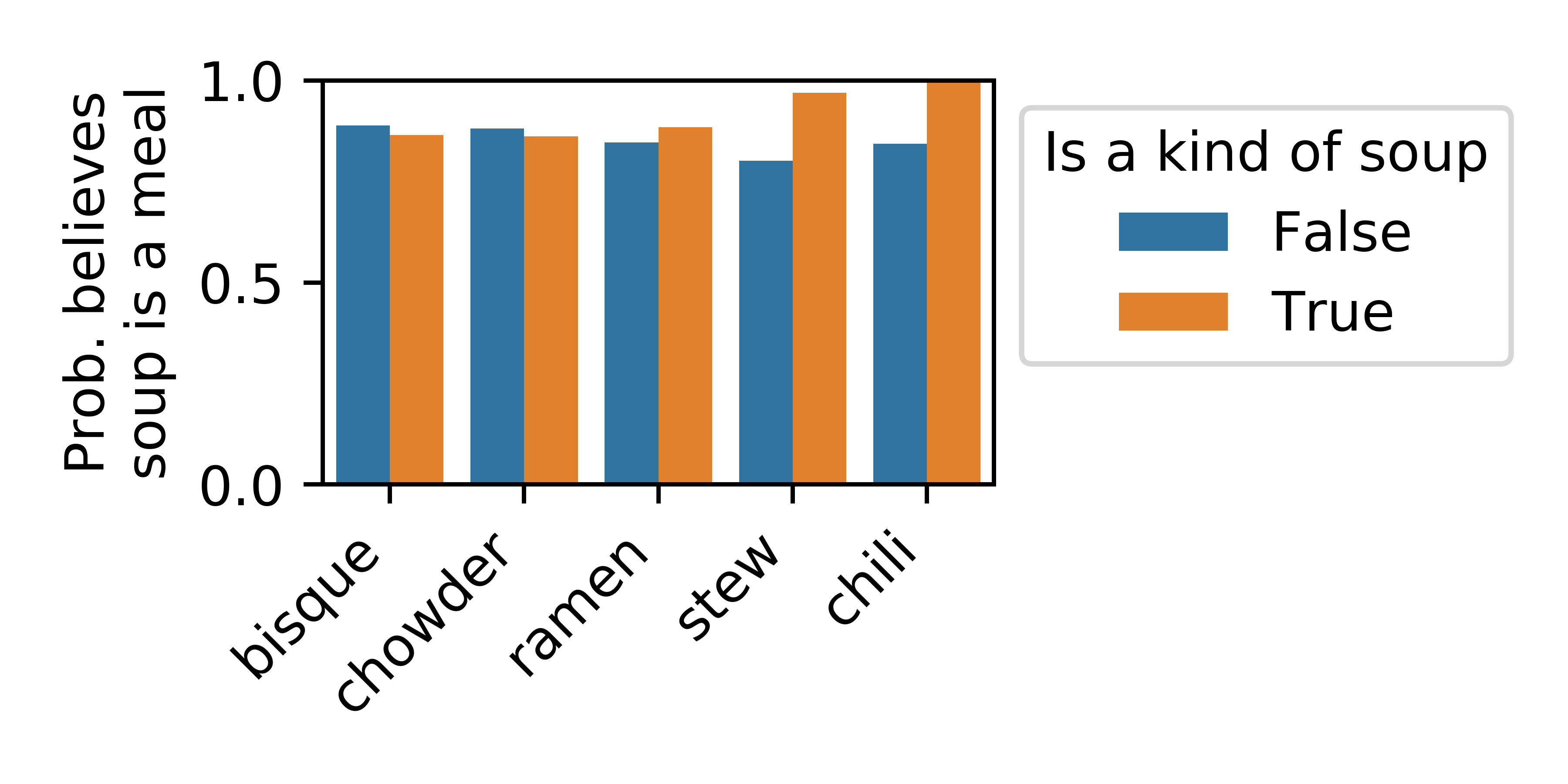

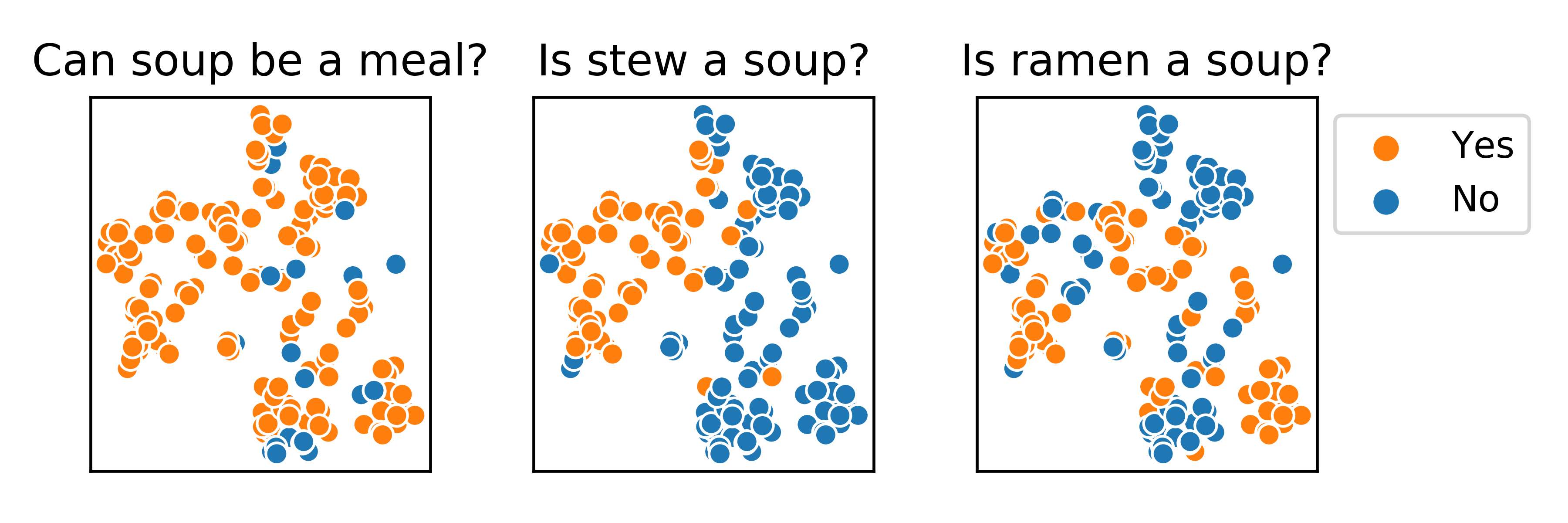

As expected, respondents labeled tomato bisque and corn chowder as soups more frequently than starch- or meat-based foods that are also served in bowls and, as noted earlier, a shockingly high number of respondents mislabeled chili as a type of soup. Our sample was divided over whether ramen and stew qualify as a type of hearty soup, or whether they belong to a distinct category (this topic was hotly debated by many participants during debriefing). Whether or not stew is a type of soup lies beyond the scope of this work, but it is nevertheless interesting to note that participants who identified stew as a type of soup were significantly more likely to believe that soup can be a meal on its own (Chi-squared p=0.00357 for complete cohort, p=0.0428 for respondents who identified as male or female and understood what soup is).

Understanding of soup is context-dependent

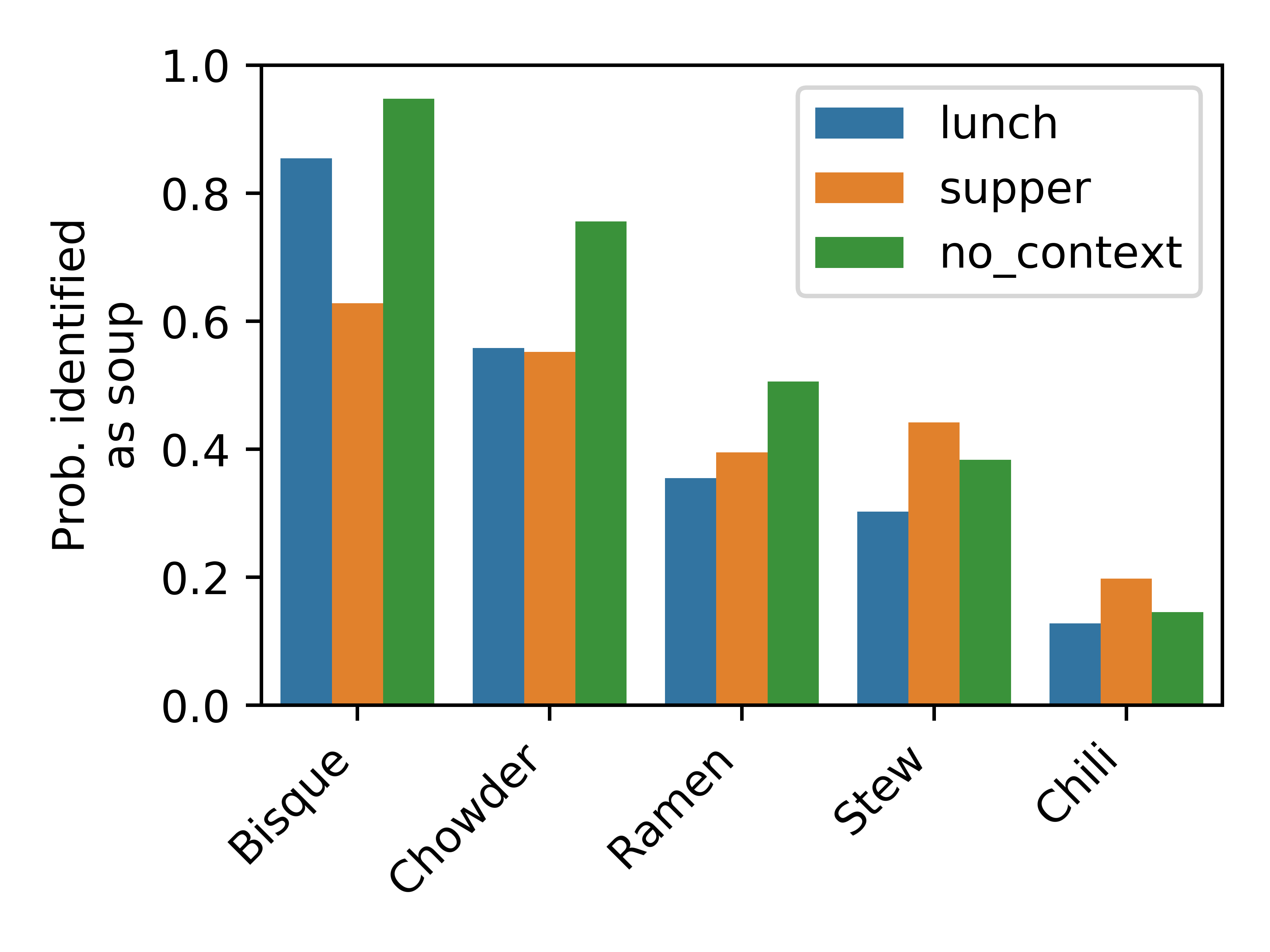

We knew from experience that it would be difficult for our participants to arrive at a logically-consistent definition of soup in order to answer this question. To better understand how people reason about bowl-based foods, we also asked participants to label the same set of foods in the context of the following two prompts.

You get a text from your friend Artemis. It says “I’m having a few people over for lunch this weekend. You should come! I’m making soup.” Which of the following do you think Artemis might be making?

You get a text from your friend Artemis. It says “I’m having a few people over for dinner this weekend. You should come! I’m making soup.” Which of the following do you think Artemis might be making?

(Emphasis added.)

Participants appeared to exhibit a bias towards light soups (tomato bisque and corn chowder) in the lunch context and towards “hearty soups” and chili in the dinner context. Intriguingly, some participants who did not classify stew or chili as soups nevertheless believed that they might be served one of these dishes in the dinner context. This may be due to a latent desire for a complete meal that is strong enough to override normal decision making, or an implicit association between soup and dishonesty.

Conclusion

Limitations of the study

Our preliminary gender-based analysis suggests that women may be more likely to believe that soup is a meal than men. Often borderline or trend-level statistical significance, deliberate attempts to influence the outcome of the study by one of the authors, and the underrepresentation of men in our sample together mean that our results should be interpreted with caution.

Because the number of gender-diverse respondents was very small, our work should be regarded as an incomplete gender-based analysis at best. The stronger association between soup belief and gender than appetite (which is probably more closely linked with sex than gender) further underscores the importance of carrying out a more comprehensive gender-based analysis than was possible here.

Business implications

Our most robust result is that a surprisingly large proportion of people are willing to accept food diluted with water as a meal. This provides an exciting opportunity for restauranteurs and other members of the food industry to profit from increasing liquidity. Our results suggest that the effectiveness of this strategy may be increased by targeted marketing to women and/or by branding the products as stews (eg “corn stew” rather than corn chowder).

Opportunities for future work

This study suggests that the soup-related miscommunications between my partner and I are at least partly rooted in gender differences in terms of how soups are perceived. In the future, a more detailed analysis of our soup dataset might begin to identify whether some of these differences are related to specific foods or contexts. Such analysis could help identify specific risk factors for the belief that soup is a meal in order to ultimately predict and prevent soup-related conflicts.

Conflicts of interest

The author discloses no conflicts of interest at the time of writing, but would welcome new conflicts of interest in the form of industry research funding or paid talks.